“The Olympics essentially represents everything that skateboarding stands against. The Olympics gives one man (or, woman) a chance to reign victorious over their peers, and bask in the ‘joy of victory’, while every other sad-ass loser gets to suffer through the ‘agony of defeat’. This is totally contrary to what skateboarding is all about. In skateboarding, you determine your own destiny. You’re not measured against other people. You’re measured against what you’re made of.”

From the essay ‘Gary Ream Doesn’t Speak For Me: Why I cannot and will never support skateboarding in the Olympics’ by Bud Stratford, freelance writer/skater.

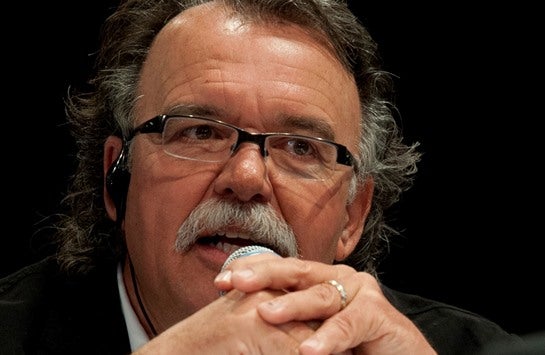

I’m looking for a free table at a reception at the end of a

long day’s work at this year’s SportAccord convention in Bangkok when I catch

the eye of a big man with a big moustache doing the same thing.

Introducing himself to me, Gary Ream adds, unnecessarily,

“the skateboard guy.” Unnecessarily, because anyone who has followed the long,

sometimes tortuous story of skateboarding’s journey to the Olympics (it will

finally make its debut at the Toyo 2020 games) knows who Gary Ream is.

He’s the former president of the International Skateboarding

Federation and now chair of the World Skateboarding Commission, a division of

World Skate, a merger between the ISF and FIRS, the international roller sports

federation, created last year in a bid to clarify the governance of

skateboarding ahead of its inclusion in the games.

The lack of a single international governing body for the

sport was one of the snags that prevented skateboarding from gaining Olympic

status for so long, and the new, merged federation is regarded by many as an uneasy

alliance between a conventional international federation complying with Olympic

rules and values (FIRS), and a body (ISF) that could command at least some

level of recognition and respect from within skateboarding’s apparently unorganised,

freewheeling, anti-establishment community worldwide.

So, who is this ‘skateboard guy’ that is expected to hold the fragile alliance together for at least the length of a single Olympic cycle (skateboarding was added to the Tokyo 2020 programme at the behest of the organising committee under new rules introduced as part of the IOC’s Agenda 2020 reform programme, and there’s no guarantee that it will be included in future editions)?

Well, for one thing, he’s not a skateboarder, and never has been, yet is a passionate advocate and evangelist both for competitive skateboarders and for the 90 per cent of skateboarders who, he says, have no interest in competing – and, at least until now, no interest in the Olympics.

Speaking earlier this week on a call from his base in Florida, he’s also intense, opinionated, contrary and, I imagine, a tricky man to disagree with, beginning with a lecture on what he calls ‘fake news’ and tales of how he’s been repeatedly misquoted in previous interviews (which makes for an uncomfortable start).

Moving on, it soon becomes clear that, far from feeling the need to defend skateboarding’s entry into the Olympics against critics such as the one cited above, he positively relishes the contradictions involved in an army of kids in back-to-front caps and baggy pants storming the bastion of the games, even as many other kids in back-to-front caps and baggy pants remain indifferent or actually opposed to them. It tickles him that an activity that was created and organised not by “adults” such as himself, but by the kids that actually practise it, has attained the holy grail that has evaded so many other, more conventional, more structured and longer established sports.

Citing Stratford’s essay, he says: “That’s exactly what I’m concerned about too! I agree with the 90 per cent of skateboarders that don’t believe in competition – but there has been competition in skateboarding for 20-some years [introduced initially by ESPN’s X Games] and it can make an impact globally and help change the thought processes of youth. The assets that [Stratford] describes are the exact powerful assets that if marketed properly can change the world.

“All the ‘Gary doesn’t speak for me…’ I get that. I don’t

speak for everybody. But I do know that the 90 per centers are as important as

the Olympic gold medallists. They have messages that have nothing to do with

competition, but with living life by way of your heart. No sport gets this deep.

“How many soccer players don’t compete? They all compete,

it’s part of the sport. But that 90 per cent are the story of skateboarding. It’s

not that easy to reach them. That is the biggest task, behind the scenes. All

the competitive side and global structure and global organisation of sport that

is, in my mind, incredibly flawed because it’s managed by government and organisations

that only worry about the position they’re voted into. There is a relatively

small percentage of passion that runs most of the global organisations of sport:

true, true love for doing what’s right every moment for the sport, not thinking

about the job, or the next vote, or where the money’s coming from. Skateboard

believes all of that but what comes first is what’s good for kids and

skateboarding.”

Having worked with kids for his entire adult life, Ream has no hesitation in backing their instinctive mistrust of those structures and organisations so beloved of his own age group (and mine). “Every day that goes by, the relevance of old people, 60 and over, compared to the relevance of youth – we are losing that battle, and life is better

because we’re losing that battle; we are all living younger. I love it! They’re

absolutely correct, they’re listening to their heart.

“Ninety per cent said, ‘We’re not doing this to be part of

the traditional sports system’. They took it up because they didn’t want to play tennis, or baseball, or

soccer. They said, ‘I don’t want to be compared, I just want to do it’. But

skateboarding has been at a high level on the competitive scene since the X

Games took it to that level, and has survived, and it’s OK. The big concern is

now throwing it onto the dinner table of the global sports scene, which means

government funding, and that can be good and bad.”

The International Olympic Committee has been concerned about

its ageing audience and has been casting longing eyes at skateboarding since at

least 2003, when Ream had his first meeting with IOC officials, and at which

point, he says, “they were not ready for us.” Within skateboarding, its Olympic

potential had been recognised for much longer, with the very first edition of

The Quarterly Skateboarder magazine in 1965 declaring: “We predict a real

future for the sport – a future that could go as far as the Olympics.”

Now, one IOC member tells me, most of his fellow members “agree

with the need to engage with the modern ‘action sports’ such as this, and

accept they add value to the programme mix, which must inevitably evolve, but

are probably wary of them actually complying with IOC charter requirements, such

as anti-doping expectations, and might well question their ‘sustainability’ as

an Olympic sport.”

A skateboarder is just a fair representation of all youth globally. It just so happens that some have taken the sport to the level of world-class athletics

Ream scoffs at this, saying: “A skateboarder is just a fair

representation of all youth globally. It just so happens that some have taken the

sport to the level of world-class athletics. They do have agents, sponsors,

contracts. Yes, they can and will conform to all policies and rules of the IOC.

Performance-enhancing drugs are not part of, or can help, the scene of

skateboarding. So we have no issues with WADA, and anti-doping, and conforming

to the rules. We have no issues other than the same percentage of issues in any

other sport.”

As for the question of sustainability, “It’s not a fad,”

Ream says. “These are multi-million-dollar athletes with sponsors and promoting

brands globally, using skateboards.”

Yet the risk of inclusion in the Olympics, critics from

within skateboarding say, is that it will somehow lose what Ream repeatedly calls

its ‘heart and soul’. What can protect it from that risk, I ask? “The biggest

protector of that is the kids themselves,” Ream replies. “Allow us

organisations and adults to impose on them what they consider is not relevant

and stupid, and they will reject the concept. The kids themselves will protect

this. It’s obviously the job of some in positions of leadership to hopefully

pave a smooth road, so that does not happen. My personal goal, which I believe is

skateboarding’s goal, is to have skateboarding enter the Olympic system and

make adjustments that we all believe are fair, but the ultimate goal of this is

to make the Olympic Games cool again for the youth.”

Those ‘adjustments’ Ream talks of are likely to be viewed with alarm by some at the IOC, with the same IOC member telling me that, upon meeting Ream, “He clearly indicated to me his view that if the IOC really wanted this sport on its programme, it would have to ‘take it as it is’, rather than try to ‘conform’ it to other sports on the programme. I smelt trouble!”

But Ream, who knows he holds a trump card in his IOC

negotiations, says: “When I was a kid, I watched the Olympic Games. I don’t

know of a kid that watches the Olympic Games today. It’s a matter of

demographics. The Olympic Games have left youth behind. I believe if you were

to ask the IOC if there is a need for an adjustment in their programming, they

would say maybe the number-one interest is to do everything possible to make

the games relevant to youth again. Think about that word, the ‘games’.

Typically, you don’t think of adults with that word. Understand that

skateboarding is maybe one of the most unique, special, relevant – I maybe

won’t use the word ‘sports’ (which it is) – but it’s a lifestyle. They live it.”

So, with two years to go until its Olympic debut in Tokyo,

what will an Olympic skateboarding competition actually look and feel like, I

ask? There will be two disciplines in the games, Ream says: skateboard street,

on a course that “replicates the plaza in front of city hall, with staircases

and handrails;” and skateboard park, which has “more facilities with ‘transitioned’

or curved surfaces and typically areas such as drainage ditches, all put together

in a concrete facility.” There will be 20 athletes per discipline, with equal

numbers of male and female athletes.

“The terminology of what the IOC calls the field of play:

that, for skateboarding, is very, very easy,” Ream adds. “It’s highly

sophisticated in the presentation of the competitive side of skateboarding.

There have been years of the X Games, the NBC Dew Tour, the professional Street

League and the Vans Park Series.

“There are very sophisticated linear and digital

presentations which are adjusted and fine-tuned because all of those

professional companies listen to the skaters. As it relates to Tokyo and the

games, it will be fairly easy, but I want to make sure we do it perfectly. I

want to make it the best ever, so we will spend a lot of time on details to

deliver a field of play at the highest level ever done in the history of

skateboarding.”

However, the success of skateboarding at the Olympics will

not simply depend on what happens on the field of play, according to Ream, who

says: “It’s so critical to wrap the youth spirit around the field of play. It’s

not just the course and stands, it’s the injection of lifestyle into the urban

centre, the activities that epitomise the heart and soul of what this is all

about: a festival village that is interactive, with music, art, fashion, video.

“Understand that” – Ream uses this imperative throughout the

interview, as if what he says is somehow beyond contradiction – “a skateboarder

progresses by watching videos, by making videos, by logging on to the internet,

by using the technology that’s in your pocket, that makes skateboarders more

influential. But video without the most important thing in life is worthless,

and that’s called music. Music is so important to a skateboarder because it’s

part of videos. It’s how they ride, they always have the ear buds in. When

skateboarders are competing, they’re in street clothing, riding a piece of art,

listening to music. And it’s not only linear or digital filming, but everyone’s

filming from the audience, then it goes on social media. So, the better technology

gets, the more influential a skateboarder gets, and all of youth in general.

Board sports are the leaders.”

Phew! Is the IOC ready for this? Does it really know what

it’s taken on? Yes, says Ream. The IOC has moved on since that first meeting in

2003. “In any agreement, or partnership, or union, it only works when it’s good

for both parties, when both parties understand each other,” he continues. “We

would not be in this situation now if I did not believe that the upper echelon

of the IOC gets it. They understand the difference, they believe this is the

future. When something this youthful comes along, developed by the kids to

world-class athletics, when was that ever done before? This is only a win-win-win

for everyone, including skateboarding.”

I’ve always believed that if skateboarding was properly protected and supported, its appearance on the Olympic stage could change the world

When the news came that skateboarding was to be included on

the programme of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, Ream was quoted as saying: “I’ve

always believed that if skateboarding was properly protected and supported, its

appearance on the Olympic stage could change the world.” What did he mean by

such a grand claim?

“If what I said previously about it being successful on the world

stage, about the field of play and presenting stories, takes place, then

there’s no question that with what is inherent in the heart and soul of

skateboarders, if presented authentically, we could change the thought process

of every youth globally,” Ream replies. “Find a mirror, look in the mirror, add

your passion of life, whatever it is, go for it, you need no other help. Follow

your passion: skateboarding could deliver that message with stories and the

field of play.”

At this point, Ream employs another of his rhetorical tactics, reducing his voice to an urgent, conspiratorial whisper, so you’re forced to sit up and lean forward to hear what he has to say, which is this: “That! Is! A! Skateboarder! No one ever dared to think that someone on a board with four wheels would be asked to come to the Olympic Games with no organisation, compared to other organised sports. Skateboarding is super-organised on a social media and technical level. Brands discover talent on YouTube. It’s way more powerful than just another sport.”

Skateboarding’s own fashion and equipment brands play a

prominent role in branding events such as the X Games. How will the Olympics

retain the authentic look and feel of such events, given the prohibition on advertising

on the field of play and venues at all Olympic events, I ask? “At all areas

where the activation is presented by brands, they’re just presenting what kids

are interested in,” is Ream’s reply. “The IOC needs to do the same thing; it’s

an opportunity to sell themselves as understanding the culture. We, through the

media, whether digital or linear, can also produce behind-the-scenes stories

that are true to skateboarding, what it is to be a skateboarder, not necessarily

those that do it to compete but those 90 per cent that do it because of the passion

that comes from your heart.

“I’m hoping along the way for some give and take to make

little adjustments for the skateboarder. Wrap a village around it that give a sense

and feel of the lifestyle of a skateboarder. Allow skateboarding to use the

production talent of true skateboarders, learned from love, sweat, tears and passion.

They are unbelievable producers.”

I’m sure they are, but the IOC already has its own highly

experienced host production company, OBS. Is Ream proposing that OBS should

take on extra skateboarding expertise to ensure that it gets its coverage of

the sport right? “Absolutely, OBS should take on experts,” he replies. “Sometimes

you only learn by crashing and burning. We have to make sure the crashes and

burns are little ones. I have learned over years and years of listening to kids

what a skateboarder is. I was helped by running some of the largest gymnastics

camps, so I always had a comparison.”

Ream was born in 1954 in small-town Pennsylvania, and graduated in business administration from Penn State University. His family was “always in business for themselves,” but instead of joining his father’s construction and food services company, he was offered the opportunity (with his father) of investing in a local gymnastics summer camp for kids; and that, he says, “turned out to be a blessing. It was not only a business and career opportunity for the future, but it also meant working with children and sports.”

He remained involved with the same summer camp organisation for the rest of his career, finally retiring from it in August last year. Now, he says, he works unpaid with World Skate, adding: “My work all relates to doing what’s right for skateboarding globally. It’s all about the Olympics.”

His involvement with skateboarding derived from 1980 when

the US Olympic team boycotted the Moscow Olympics, a regular “high point” for

gymnastics. “We knew that would hurt our clientele,” Ream says, “so we went

looking for other sports.” Initially, he and his colleagues identified BMX

cycling and, having built the ramps and jumps required at the camp, skateboarding

quickly followed.

His first brush with the IOC came with that meeting in 2003

when he was invited to Lausanne to address its officials on the subject of

youth culture – not specifically on skateboarding – although he is hazy about

how the IOC came to identify him as a spokesman for that (to them) no doubt

alarming phenomenon. “They asked if I wanted to assist to look to organise the

sport in a way that was conducive for entry to the Olympic Games,” he says,

adding: “I had serious doubts. It’s all about timing, and back in 2003 there

was no use to force issues that weren’t made to be. All we knew was that, if

things continued to progress, that some day it would make sense, but in 2003 there

was no need to be part of the games.

“It [skateboarding] was an unknown commodity to the global

sports world, even though a few of us knew that this was real. But you always

want to go to a party you’re invited to, not one you just show up to. You want

to be wanted, but to know why you’re wanted. We had to wait until they knew why this was important, rather than just

that it was important.”

At our first meeting at SportAccord, Ream spoke to me with emotion about the death of his son Brandon, aged 29, from cancer in 2014. Brandon was vice-president of operations at Ream’s summer camp organisation, and although it’s a delicate subject, I ask whether that tragedy influenced and informed Ream’s campaign for skateboarding to join the Olympics. Did he feel he was in some way doing it for Brandon?

“First, there was never a desire for me to absolutely get

skateboarding into the games,” Ream replies. “My son knew that. All we knew was

that skateboarding could be a tool to change the world. And, yes, my son does

have a lot to do with this because, although he was a traditional sports

participant [not a skateboarder], he knew the passion and influence of a skateboarder.

He grew up with these sports at camp and he, with his own eyes, understood the

difference. That’s the difference that he knew we had to protect and if it

meant not going to the games, OK. But if we do go, it was, ‘Dad, we’ve got to

do it right’.”

The chances of us not being in future games are slim to none. This is maybe the most important thing the IOC has done for youth, ever

And what about skateboarding’s Olympic future? With no

guarantee of a place on the core programme, is it destined to be included or

left out randomly in future, at the whim of future host cities? “I believe it

will be successful,” Ream replies. “I believe it’s bringing to the games what

no other sport can, other than surfing and snowboarding. I have no concern

about the future. If it’s not part of the future, that was probably meant to be

and that’s OK for skateboarding. In my mind, there’s no pressure, just an

understanding that we’re OK either way. But the chances of us not being in

future games are slim to none. This is maybe the most important thing the IOC

has done for youth, ever.”

Although not a skateboarder, Ream has been involved in

playing sports all his life. “The biggest is basketball. I played in a

competitive basketball league until I lost my son. I played until he could play

with me, but then when he got sick, no more basketball. But I play golf –

anything that relates to games, I’m in.”

So what is sport for, I ask? “There’s no question that sport is a major, major, major plus in life,” he replies. “Sport teaches you everything in life, as relates to working together, working for a goal… Sport is life and it’s a beautiful blessing for anyone that discovers sport. The thing I do believe is skateboarding is way, way, way more than sport. It has all the aspects of life within that traditional competitive side, but it’s endlessly deeper than any sport that I know. It is life, true youth creativity and freedom, and it’s ever-changing. The two words that are very big warning signs for all of us are organisation and adult intervention, control. Organisation means rules, rules and rules. It’s not that skateboarding has no rules, but they’re rules that they [skateboarders] create in a structure that works for them at that particular moment.”

And what would success for skateboarding at the Tokyo 2020

games look like to Ream? “It would be the skaters on the street making the

comment, ‘Wow, the Olympic Games got it’,” he says without hesitation. “’They

got it right. Amazing!’ That’s the win: ‘We don’t agree with it but, boy, did

they get it right!’”